When Communication Became a Battlefield: Reclaiming Attention in the Wild West of the Internet

- Nathaniel Hope

- Oct 7, 2025

- 25 min read

The world is connected. It’s a 24/7 machine, humming with activity in every corner of the globe. The internet absorbs it all like a living creature, digesting the constant churn of news, updates, and stories, then spitting it back at us in endless streams. Some of it is free—or, you know, “free.” Free in the same way a “free sample” at the grocery store is free: you’re not paying in money, but they’re betting you’ll buy the whole box. Online, it’s your attention that’s for sale. You get the article, but you also get the banner ads, the trackers, and the sudden wave of targeted shopping suggestions for that one pair of shoes you Googled six months ago. Congrats—you didn’t pay with cash, you paid with eyeballs. And when it’s not “free”? That’s when you hit the gates. Some of it is locked behind paywalls. Some of it dangles just out of reach with a pop-up: “Sign up for our newsletter to continue.”

And then there are the worst offenders—the sites that make you regret clicking at all. You know the ones: pop-ups firing like fireworks, windows stacking on top of each other so fast you feel like you’ve opened a portal to digital hell. One box flashes red: “Your computer is infected!” Another one shouts that you’ve won a gift card (spoiler: you haven’t). A robotic voice warns you to “call immediately” and type in your credit card number to “fix the problem.” All you wanted was to read an article, and suddenly you’re playing Whack-A-Mole with scam alerts and shiny fake download buttons. It’s like the internet equivalent of being chased through a carnival funhouse—except instead of mirrors, it’s just lies stacked on lies. Hard to believe, but it wasn't always this ridiculous. Once upon a time, news and stories were simpler to access.

In the decades that predated the internet—shoutout to the 80s generation out there—the rhythm of information was steady, predictable. You had the local TV broadcast, usually at six for the early evening report and again at ten, after the sitcoms wrapped. Anchors would sit at heavy wooden desks, shuffling papers as the cameras zoomed in, their voices delivering the day’s headlines in half-hour blocks. If you missed it, you waited until the next broadcast. There was no endless scroll, no breaking alerts lighting up your pocket. News arrived on a schedule, and everyone in town tuned in at the same time. Print was just as central. You either subscribed to the paper or grabbed a copy at your local corner store. Quarters bought you headlines, comics, classifieds, and the day’s stories pressed in black ink that rubbed off on your fingertips.

A subscription meant the paper landed on your porch each morning with a satisfying thump. Sunday editions were thick with inserts and glossy ads, sprawling enough to spread across the entire kitchen table. Reading the news was a ritual: coffee, paper, maybe the radio humming in the background. And radio was its own part of the puzzle. Commuters tuned into AM stations for traffic updates, weather, and breaking stories. Families kept FM on in the kitchen, catching news bulletins every hour between songs. You didn’t “refresh” anything—you waited for the top of the hour, the DJ’s voice sliding in between commercials. News slipped into your day in steady intervals, not through constant notifications. TV, radio, and print didn’t compete with each other—they overlapped, forming a rhythm of information you could trust. You knew when and where to get it, and once you had it, you moved on. And when it came to print, distribution was everywhere.

Stacks of local papers by the register at 7-Eleven, racks inside grocery stores, those quarter-fed kiosks lined up outside supermarkets and bus stops. Bigger names like USA Today and The Wall Street Journal managed national reach, so you might find them in airports or hotels across the country. But for the most part, what you read was whatever your region printed. If you lived in California, you got the Sacramento Bee, the San Francisco Chronicle, or the L.A. Times. If you lived in Washington, you got the Seattle Times. Want the New York Post? Unless you were in New York, good luck.

These days, if you want to read anything—The New York Times, The Atlantic, even your hometown paper—it’s not waiting quietly on your porch or bundled at the corner store. Sure, newspapers still exist, and you can still get one tossed onto your driveway if you really want, but it’s not the default anymore. And TV? Radio? They’re still around, but let’s be honest—what used to be reporting has turned into round-the-clock opinion shows dressed up as news. Shouting matches, now in HD. The internet didn’t fix that; it just turned up the volume. Suddenly every platform has its own “take,” and every person with Wi-Fi has a soapbox with the volume knob stuck at max.

So when the evening news feels more like a debate club, when the morning paper’s gone missing from the porch, and when even radio can’t go ten minutes without an ad break—where do we go instead? Well, these days, most of us default to the web. And once you’re there, it feels like you need a subscription for everything. But it doesn’t stop there—they don’t just want your money; they want your email, too.

They want to slip into your inbox, stack your promotions tab with newsletters, and follow you onto your phone with push notifications. And it’s not just the papers. Every website is a gate now. Instead of one front page delivered once a day, you’ve got dozens of digital doors—each one demanding a password, an account, a sign-up, a monthly fee. You don’t flip through a Sunday edition with inky fingers; you juggle pop-ups, paywalls, and “limited free article” counters. Back then, the news came to you. Now, you have to chase it—and pay for the privilege.

It’s kind of crazy when you think about how much the internet has given us and what it’s become. The internet hasn’t given us fewer gates. It’s multiplied them. And that’s where the problem begins.

When Email Became the Landfill

That’s the thing about the internet: it didn’t just multiply gates, it also reshaped the way we pass through them. The paper on the porch became newsletters in your inbox. The evening broadcast turned into alerts and subject lines. What used to arrive in neat, predictable packages now drips into your life one notification at a time. The medium changed, but the promise stayed the same: connection, delivered instantly.

On paper, newsletters sound like a modern replacement for the folded newsprint of yesterday. But in practice, they’ve turned the inbox into something more like a junk drawer. Ironic, considering every email service already has a “Spam” or “Junk” folder built in. My argument? The entire concept of email—once hailed as a futuristic revolution that would connect people across the globe—has become its own junk drawer. Think about it. Almost every website you visit, every store you shop at, every article you read has a newsletter waiting for you. And they don’t exactly play hard to get. Make an online purchase and forget to uncheck those little pre-filled boxes? Congratulations—newsletters are on their way. Subscribe to just a handful and suddenly your inbox floods: new stories, urgent alerts, “last chance” sales, all piling on top of work messages and family updates.

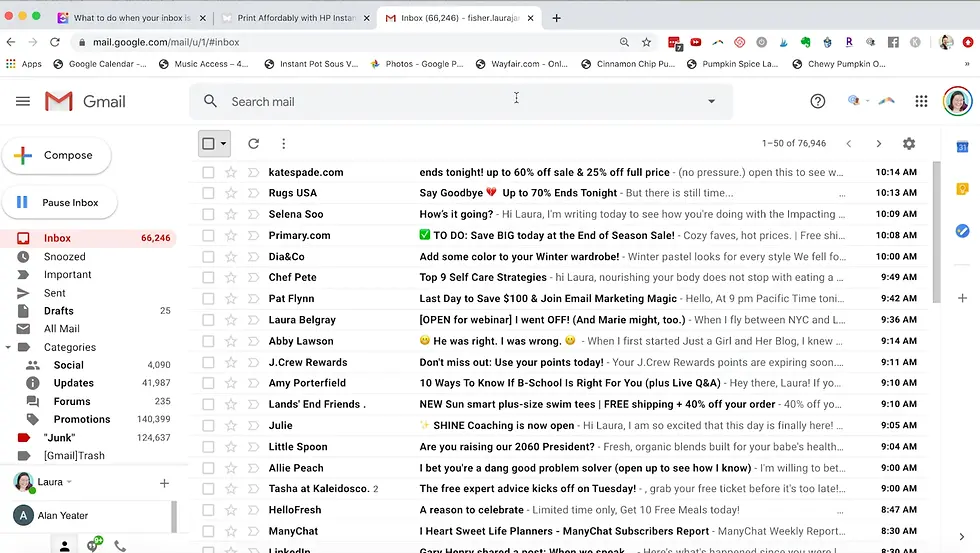

Sure, apps like Outlook and Gmail try to dress it up. Outlook, for example, has been the standard in offices for decades. I’ve used it at my job for over ten years, and honestly? After all these years, it’s still overwhelming. There are folders, categories, flags, rules, focused inboxes—you name it. It’s all there, but you’re left to figure out how to manage it yourself. If you don’t stay on top of it, Outlook just turns into a wall of unread subject lines, no better than a messy desk where every paper is marked “urgent.” Gmail takes a different tack. It comes with a general inbox, a social tab, and a promotions tab right out of the box—like it’s politely saying, “Here, let me sort this chaos for you.” Except the filters don’t really kick in until you teach them, and most people never bother customizing anything. They just let emails pile up, the same way junk mail piles up on the kitchen counter until you finally snap and sweep it all into the trash. Take my own inbox, for example My Gmail promotions tab? It currently has over 6,030 unread messages. Six thousand and thirty. Let that number sit for a second. That’s not an inbox—it’s a digital hoarder’s attic.

And here’s the kicker: if I didn’t have filters or rules in place, all of that would be sitting in my main inbox. Can you imagine? At that point, it’s not even mail anymore—it’s a landfill with a search bar. And let's be real: I’ve long since given up on “Inbox Zero.” At this point, I’m just aiming for “Inbox Manageable Without Inducing a Panic Attack.” Every so often I’ll highlight the whole mess and hit delete, just to get that fake clean-slate feeling. And within hours, the cycle starts all over again. Sometimes I crack and hit “unsubscribe” just to stop the noise. Classmates.com, I’m looking directly at you. Seriously—I don’t care who just viewed my profile. I don’t need an email for that. Yes, I updated my settings. Yes, I turned off that feature. Yes, I’m still getting the emails... But I digress. Here’s the thing: unless you’re building intricate filters, actively pruning your subscriptions, and staying on top of it like some kind of digital gardener, your inbox turns into chaos. A place you dread opening. A place where it’s easy to miss what actually matters.

And I see that every day, not only at home, but also at work.

"I sent you an email" doesn't carry the weight it used to

For those who don’t know, by day, I’m a Technology Specialist for a school district. Back in the day, you would’ve just called me a computer technician. But schools have way more going on now than just computers, so my job touches just about everything involving technology—phones, Chromebooks, projectors, printers, you name it. I love it, honestly. It’s never boring, and I get to help everyone: teachers, students, secretaries, principals, custodians, and more. It’s a very rewarding and fulfilling job. That being said, try getting any of them to actually read their email.

Last summer, we had this big project replacing every phone in every classroom and office across the district. These aren’t the old plug-in-the-wall phones anymore—they run on Ethernet, which puts them on the network and under our department. Well, guess what? Our department sent emails out explaining the what, why, when, and how. But once the project got rolling? Chaos.

Nobody seemed to know why the phones were changing or how to use the new ones. One of our associate superintendents even walked into her office one morning to find a shiny new phone on her desk. First thought: “Cool, but how the heck do I use this?” When it was mentioned that our department had previously emailed instructions, and I couldn’t help but laugh. This is a person responsible for a massive chunk of the district, swimming in emails every single day. Do you really think those instructions would be sitting at the top of her inbox in that exact moment? No chance. That’s the reality: the phrase “I sent you an email” doesn’t carry the weight it used to. Not because email is useless, but because it’s buried alive. Between tech help tickets, memos, staff replies, and the inevitable flood of district-wide spam, it’s not hard to miss an email. Honestly, it’s harder not to.

And yes, in my workplace there’s definitely an overreliance on email. But so are hundreds—if not thousands—of companies out there with the same problem. Sure, I’ll admit, our department could’ve done more than just “send an email” and call it a day. Heck, every department is guilty of it. Communication’s messy, and there’s always room to get better. But that’s the conundrum, isn’t it? We all rely on email as the go-to tool for communication. Every one of us. The problem isn’t just what we say—it’s the system itself. The way email is built, the way information gets passed along, almost guarantees that messages get buried. Flooded, even. And when your inbox is already drowning, it doesn’t take much to push it over the edge. Think about your own inbox for a second. Doesn’t matter if it’s Gmail, Outlook, Yahoo, AOL (yes, they still exist), iCloud, or whatever service your company uses. At the end of the day, it’s just a stack of words on top of words—messages piled high until they blur into noise.

Case in point: we’ve had email for decades now. You’d think by this point it would’ve evolved, maybe even gotten better. Instead, it feels stuck in the past—like everyone’s just copying each other’s homework. Nobody’s really tried to redesign it, give it some flair, or make it a place you’d actually want to spend time in. And the bigger issue? For a tool that was supposed to revolutionize communication, you’d think people would’ve figured out how to use it by now. But here we are, in the year of our Lord 2025, and half the district office is still hitting “Reply All” just to thank the person who brought in freshly baked cookies—Which, for the record, were gone by the time I got there. And it’s not just "Reply All". Flagging an email as “urgent” or “important”? Sounds good in theory. But once it’s stacked under a dozen new messages, it’s as good as gone. And if you’re the type who marks every outgoing message as urgent—only for me to realize they’re not—well, eventually I stop taking you seriously. Honestly, I might ignore you outright. That constant pile-up makes it harder to navigate both work and home life. And that’s something we, as a society, really need to address.

Email used to be the reliable signal. Now it’s mostly noise. And that’s the saddest part: what was once magical—the “You’ve Got Mail” thrill of the AOL era, when messages felt instant and revolutionary—has become a place of dread. If you grew up in that time, you can probably still hear the voice in your head. Back then, it felt like the future. Today, the magic’s gone. Email didn’t evolve with the rest of the internet. Instead of being the beating heart of communication, it turned into the landfill of the digital age with ads. And nature abhors a vacuum—so something else had to fill the gap. That’s how social platforms rose, not as a cure, but as the next distraction we willingly stepped into. Not because they’re perfect, but because they’re where we actually want to spend our time.

Social Media: The Accidental Hub

Social media didn’t set out to replace email, but it ended up filling the space email left behind. It became the accidental hub—where posts, comments, and conversations pile up the way letters once did in an inbox. Meanwhile, email has drifted into obligation: receipts, password resets, meeting invites, and long threads you never asked to be copied on. Facebook, X (RIP Twitter), Instagram, BlueSky—scroll long enough on any of them and you’ll trip over breaking headlines, hot takes, or that one friend from high school posting about conspiracy theories. If something grabs your attention, a click takes you to the publisher’s site, where the familiar “subscribe to continue” wall inevitably waits. The irony is almost comedic: the algorithm spoon-feeds you an article, then the site itself slaps the fork out of your hand. And more often than not, that slap comes with the same old move—“Sign up for our newsletter to keep reading.” Which, of course, just dumps you back into the inbox mess you were trying to escape in the first place.

And here’s the thing: for all their flaws, social platforms became better at delivering news than email ever was. Nobody opens Gmail to be inspired—it’s utility, not community. But people do log into Facebook, Instagram, or X to kill a few minutes, catch up with friends, or see what’s trending. That’s the hook. Social media is sticky in a way email never figured out how to be. Articles aren’t just dropped into a static inbox—they’re wrapped in conversations, memes, hashtags, arguments, and infinite scroll. You don’t even have to go looking for news. The algorithm brings it to you, whether you asked for it or not.

It’s the carnival midway of the internet. Flashing lights, music, voices shouting from every booth—each post competing for your time and attention. Some stalls are fun, some are scams, and plenty are just distractions dressed up as something urgent. You can’t stroll through quietly. Every scroll is like someone tugging at your sleeve, promising you’ll miss out if you don’t stop and play. And sometimes, I’ll admit, that feels like magic. You stumble across an article you never would have searched for, or a story that opens up a whole new rabbit hole of curiosity. That’s the fun side of serendipity. But the flip side? It’s exhausting.

The feed isn’t curated by you, it’s curated for you, and not necessarily with your best interests in mind. The algorithm doesn’t care what’s true or false, only what’s engaging. Which means outrage, clickbait, and the same recycled headlines float to the top while quieter, more meaningful things often sink. You never know if you’re seeing the whole picture—or just the version of it designed to keep you scrolling. And then there’s the pressure. Email may bury you, but social media puts you on stage. Post an article or share a thought, and suddenly you’re waiting for likes, shares, or comments to trickle in. Sometimes you get a lively discussion. Sometimes you get the toxic corner of the internet. Other times, silence. Either way, you can’t help but measure it. Social platforms turned information into performance. Email never did that. An email lands in one inbox. A social post lands in a crowd. And that crowd can be loud, judgmental, or eerily quiet.

And even when you try to step away from the crowd, there are the DMs—“direct messages,” basically the grown-up version of passing notes in class. Facebook has Messenger, Instagram has its inbox, X has DMs, LinkedIn… well, LinkedIn has that one random recruiter who somehow finds you no matter what. And then there’s WhatsApp, which feels like a hybrid between texting, calling, and dropping voice memos at all hours of the day. It’s the go-to messaging app for huge parts of the world—Europe, South America, Asia—though here in the U.S., it’s more of a “you either use it or you don’t” kind of thing. Not exactly like email, but all of them are ways to talk directly to people—and while that sounds convenient, it usually ends up feeling more like pressure than connection.

These side apps feel like modern versions of AOL Instant Messenger or MSN Messenger—except worse, because now there are read receipts. Kids today will never know the stress of crafting the perfect “away message” to dodge conversations. For me, that’s part of why I can’t stand using them now. Friends and family message me all the time—which, don’t get me wrong, I genuinely appreciate—but the second I click that bubble, it yanks me out of the feed and drops me straight into obligation mode. And it’s not about the people on the other side; it’s about the way DMs are built. The moment you open one, the read receipt flips on like a spotlight, and suddenly you’re expected to perform. You’re typing, they’re watching, you’re aware of it all in real time. Or worse—they see you read their message, you don’t respond right away, and now they’re left to wonder if you’re ignoring them. You’re not, but the pressure makes it feel that way.

Honestly, it’s the same reason most of us don’t pick up the phone anymore. Caller ID turned every ring into a gamble, and spam callers only made it worse. Carriers like Verizon even build scam filters into their service now because it’s gotten so bad. So what do we do? We let the call go to voicemail. And nine times out of ten, that voicemail is just ten seconds of silence before a hang up. That simple act of connection—just answering the phone—got buried under years of scams and noise, the same way email drowned in newsletters and DMs drowned in read receipts. And honestly, that’s when it hits me: it’s not just one app or one platform. The whole internet is playing the same game, pulling from the same playbook designed to keep you staring at a screen.

The Bigger Picture: Fighting for Our Attention

Step back far enough, and the pattern becomes obvious. It’s not just email. It’s not just social media. It’s the entire online ecosystem, rebuilt piece by piece to make sure you never look away.

Take our phones, for example. I personally have a Samsung Android phone. If I swipe right, it lands me on a news feed powered by Google. For all you iPhone users, swiping right takes you to the Today View with Apple News headlines front and center. Different phones, same idea—the news is waiting for you whether you asked for it or not. Just like social media, I can curate the topics: news, entertainment, pop culture, politics. Honestly, I’ve found it slightly more interesting than doom scrolling Facebook because at least the articles are front and center. Many catch my eye, intriguing me enough to want to read more. But this is where the magic of wonder and curiosity disappears.

The article starts to load, and almost immediately, up comes a pop-up: “Continue reading with a subscription.” Some companies are sneakier—Fortune, for example, will let the first paragraph load before blurring out the rest and dropping the subscription window. And if you look at places like The New York Times, The Atlantic, Bloomberg, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, the L.A. Times—they all get you into the article only to immediately start asking you to subscribe. Maybe part of the issue is Google’s fault. They curate articles for me based on my interests, but the moment I click one, I’m immediately hit with a paywall. And look, I get it—nothing is free. These companies need to make money. But from my side of the screen, the end-user experience is maddening. It feels like every door I open on the internet slams shut unless I’m willing to pull out my wallet. Most of the time, I just back out, search for the same topic elsewhere, and hope I can find a version that doesn’t try to twist my arm just to let me read. And for the sites that don’t lock everything behind a paywall? You still get a pop-up—this time the obligatory “Sign up for our newsletter” or “Enter your email to continue.”

Then there are the sites that want you to “sign in to continue.” Not just subscribe—sign in. They want you to create a profile, as if their site is its own little social media hub where you can start threads, review, rate, and comment. Which is ironic, because most of the time I’m not there to build or join a community. I’m just there for the article that caught my eye. Let’s be honest—the crowd’s already hanging out on the big apps: Facebook, X, Instagram, BlueSky. Nobody’s saying, “Hey, meet me in the comments section of Bloomberg.” That’s not why I clicked. But the second I step inside, I’m immediately asked to stay, register, sign up, pay, donate—whatever. It’s like—dude, I just got here. I don’t need a pop-up demanding my loyalty any more than I need an email telling me someone clicked on my profile from 2007. I’m only interested in the one thing that brought me here. Why am I being asked to make a commitment before I’ve even had a chance to look around?

The internet, in a nutshell, is like walking through the front door and immediately being swarmed by a pack of kids all yelling at once—“Play with me! Look at this! Sign this permission slip!”—and you’re still just trying to take your shoes off. And in that moment, all I want to do is turn around and walk right back out. Make a lifelong commitment when all I came for was the recipe from that dope nacho video someone posted on Facebook? Yeah… I’m good. Maybe it’s just me, but after years of watching the internet shift under my feet, I’ve been forced to build my own defense mechanisms. And it’s all because of these experiences—these bombardments, these never-ending “in your face” tactics. I don’t know about you, but it’s a huge turn-off.

My lifetime of personal and professional internet use has trained me to expect these patterns: the pop-ups, the “too perfect” headlines, the little manipulations that nudge you into handing over more time, more data, more attention. These tricks I’ve meticulously developed help me decide whether to stay or move on, whether something’s worth my time or just another trap. Am I proud of myself for crafting these skills? Not really. I mean, yeah, sure—in the long run, I’m protecting myself from all the different ways I could get scammed. But even with all that awareness, having to stay hyper-conscious of so many little things is exhausting. The giant green “Download Now!” button that’s somehow not the download button. The tiny “X” in the corner that’s basically a trap door to three more pop-ups. Or the email that swears it’s from my bank—but apparently my bank now writes in Comic Sans and signs off from “Steve, Customer Care.” It's just maddening. And if I’m feeling this way, I know I’m not alone. Because this isn’t just about me being cranky at my inbox—it’s a shared experience, and the human cost of this constant tug-of-war for our attention is everywhere.

People skim headlines without ever reading the story because they’re too tired to fight through paywalls. Others abandon their inboxes altogether, letting thousands of unread messages pile up until the number itself becomes another source of anxiety. Doom scrolling has become a cultural joke, but it’s not funny when you realize how much time we lose to it, or how heavy it feels to carry all that outrage, tragedy, and noise. Even our relationships aren’t immune—friends and family messages end up buried between marketing blasts, work memos, and scam attempts. The lines blur, and suddenly everything feels like noise.

And the cost isn’t just personal—it’s cultural. When people are too overwhelmed to read beyond the headline, trust in information erodes. Nuance gets lost, outrage fills the gap, and suddenly our collective understanding of the world is reduced to clickbait and soundbites. The constant overload doesn’t just drain our energy; it eats away at our ability to focus, reflect, and connect in meaningful ways. It leaves us cynical, less likely to engage, and more likely to tune out altogether. And when whole communities start tuning out, the very idea of being informed—of sharing a common picture of reality—starts to break down. But here’s the thing: this collapse of attention didn’t just happen on its own. It was engineered. The reason every site throws pop-ups in your face, the reason every inbox feels like a war zone, comes down to incentives.

Online advertising collapsed into a race for clicks, so publishers turned to subscriptions to survive. Social platforms discovered that outrage and endless scrolling keep us glued longer, which translates directly into profit. Data became the most valuable currency, which is why so many sites don’t just want you to read an article—they want your email, your profile, your habits.

The attention economy isn’t just a buzzword. It’s the business model.

Rethinking Connection

Like I said earlier, this may have started with looking at my inbox. But stepping back, it’s bigger than that. The internet, as it exists today, has been redesigned piece by piece to fight for our attention—it's messy, it's chaotic, and it never stops. Once you see the patterns—the pop-ups, the paywalls, the “must-read” alerts—you can’t unsee them. And that realization is both exhausting and liberating. Exhausting, because it means the system really is rigged against focus. Liberating, because once you recognize the tricks, you can start choosing when not to play.

So the question is: what now?

Honestly, when I sat down to write out my frustrations with the internet—the paywalls, the pop-ups, the inbox noise—I kept circling back to that same question. What do we do with this mess? Because I know exactly what would happen if I posted any of these frustrations on places like Facebook or YouTube. Some troll would drop in with the classic “Welcome to the Internet” reply.

And sure, it’s funny. It’s also kind of a mood—a cultural shrug we’ve all internalized. Someone points out, “Hey, this place kind of sucks,” and the crowd responds, “Yeah, we know. That’s just how it is.” But here’s what gets me: what wears me down is that mentality—that shrugging, “nothing we can do about it” sense of defeat. Maybe after years of companies fighting for our attention and trolls hiding behind screens trying to scam us, maybe as a society we’re just exhausted. Because I honestly don’t see enough people calling any of this out. I don’t see many conversations about the internet as an entity—what it’s become, how it’s designed, and why it grinds us down. And heck, maybe I don’t see it because the algorithm is hiding it from me. Who knows. What I do know is that we joke about doom scrolling or “Inbox Zero,” but we don’t ask the bigger question: Can it be better? That’s the conversation I want to have.

Because underneath all the noise, all of these tools were once built on something simple: the most fundamental thing we all long for—connection.

Email used to be about connection. Social media used to be about sharing. Both got swallowed by the attention economy and turned into obligation machines. But the tragedy is also the opportunity. These tools could still be powerful—if we reclaim them. Email is universal. Social media can amplify voices that never had a platform before. Even the humble newsletter could be more than another “last chance” sale—if it remembered what it was meant to be: human connection.

The internet doesn’t need to be burned down and rebuilt from scratch. It needs to be rebalanced. Right now, even after all these years, it still feels like the wild west. But today’s internet isn’t one town—it’s a thousand saloons lined up side by side. Amazon’s hawking goods at one end, TikTok’s throwing a dance party at the other, and the rest are all yelling for your attention in between. Nobody’s going to “fix” that. But maybe the way forward isn’t waiting for some billionaire to reinvent the internet on our behalf. Maybe it’s carving out smaller, saner spaces for ourselves.

But here’s the other side of that coin: plenty of articles and videos preaching the same answer—just disconnect. And sure, for some people, that’s easier said than done. Internet and social media addiction are real, and they run deep. There are people who genuinely struggle with it, who don’t know how to escape or where to find help. The unhealthy extremes exist, and they shouldn’t be brushed off. For me, I’m not speaking from that place. I’m not trapped—I’m just frustrated. I can see the patterns, I can step away when I need to, and I still find small pockets of joy online. But even from that position of control, the idea of “just quit” doesn’t sit right with me. Because it doesn’t really fix anything. At best, it gives you some personal peace, but the system itself stays the same. Walking away doesn’t change the problem—it just leaves it untouched.

The better answer I’ve found has been to simplify. It’s not perfect, but it’s made things better. I used to be on everything—MySpace, Friendster, Vine, Google+ (remember that one?), Tumblr, Mastodon, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Threads, BlueSky. And as a musician, I was juggling the music side too: MySpace Music, Last.fm, SoundClick, SoundCloud, ReverbNation, Bandcamp, and more. Looking back, that’s… a lot. But I came from the generation where the internet felt magical, revolutionary. Every new platform felt like a fresh frontier, and it was genuinely exciting to dive in.

But over the years—especially this past year—I’ve scaled back. A lot. Part of it is personal, part of it is cultural. Like I said earlier, internet and social media addiction are real, and they run deep. There have been countless studies on how addictive social media can be—how it taps into the same reward systems as gambling, feeding you little dopamine hits every time someone likes, shares, or comments. And I’ve felt that firsthand. Facebook in particular always made me anxious, like I was stepping onto a stage every time I posted. Say the wrong thing, and you’d get heckled or trolled. Say nothing, and you’d wonder if you were invisible. Even when things went well, there was that nagging voice: "How many likes did I get? Who responded? Did anyone care?" It turned connection into performance, and after a while, the pressure wasn’t worth it. So, I barely post on Facebook anymore. I didn’t quit outright, but my participation has definitely dropped way down. When I do post, it’s usually something positive I want to share; otherwise, I just skim headlines or check in on friends and family. Twitter—or X, as it’s now called—I abandoned completely. To quote Obi-Wan Kenobi: “You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy.” The toxicity of that entire platform was exhausting, and I finally decided I’d had enough. Instagram? For all its visual polish, Instagram just turned into a smaller version of Facebook. Even Threads, their attempt to mimic Twitter, felt like more noise. The rest? They either fizzled out—bought up, shut down, or just forgotten—or I left them behind because something else had grabbed my attention. After years of bouncing between platforms, I realized I was simply exhausted—and it was time to make some personal changes. These days, while I still poke my head into Facebook once in a while, Discord is where I actually spend a lot of my time.

It started with Twitch—watching streamers I liked and connecting with their communities in real time. When the streams ended, the conversations kept going on Discord. When I was streaming myself, our little corner of Twitch found new life in our own server. And honestly? It’s been amazing. Just talking, sharing, and connecting with people the way it used to feel back in the early days of the internet, when things weren’t so loud or so complicated. I don’t stream much these days—being a dad has reshaped my priorities—but I still have that community.

And honestly? There’s something special about that.

But even beyond social media, there’s more we can do. It might mean building tools or setting boundaries that put us back in control, even if just a little. We can’t fix the whole system overnight. But we don’t have to accept the defaults either. Because at the end of the day, the internet isn’t just code and corporations—it’s us. It’s always been us. Sometimes that looks like a Discord server. Other times it’s niche forums and small online groups—those old-school, interest-based communities. Yes, they still exist. The internet isn’t just Facebook dragging you into a political flame war or TikTok feeding you endless clips of squirrels on jet skis. There are places like a cooking subreddit, a board game forum like BoardGameGeek, a D&D group on Discord, even a modding hub like Nexus Mods. And when you stumble into the right one, it really does feel like discovering a hidden gem. They’re not about algorithms or outrage; they’re about people showing up because they care about the same thing you do. It’s a quieter kind of internet, but sometimes that’s exactly what we need.

And maybe even email—buried as it is—can be reclaimed in small ways. The system itself feels broken; the internet makes it far too easy to drown us in unnecessary messages. Most of the time, it isn’t even our fault. There’s a reason they call it spam. But until that system gets a real overhaul, maybe we can still salvage pieces of it. I’ve unsubscribed from more lists than I can count, but every once in a while, a newsletter actually feels worth it. A personal note from a writer I admire, an update from a project I care about—those little sparks remind me why email mattered in the first place. Just like we can carve out quieter corners outside the chaos of social feeds, we can do the same with our inboxes. Not perfect—never perfect—but better. A couple of newsletters we actually care about, a few voices worth hearing. Email doesn’t have to die. It just has to feel less like a landfill—and more like something you’d actually want to open without sighing first.

And if we can reshape even a small corner of the internet to feel more human, maybe that’s enough to start tipping the balance back toward connection. They say the world is what you make it, and the same goes here: the internet is only as good as the pieces we build inside it. Even small steps—building communities, setting boundaries, reclaiming space—can add up to something better. In the end, maybe that’s the fix—not chasing every notification, but protecting the spaces where connection still feels real. The internet will probably always be the wild west, a thousand saloons shouting for your attention. But if you can find even one place that feels steady, honest, and human—one corner where the signal finally cuts through the noise—maybe that’s enough.

Thanks for reading.

Sincerely,

Nathaniel Hope

Comments